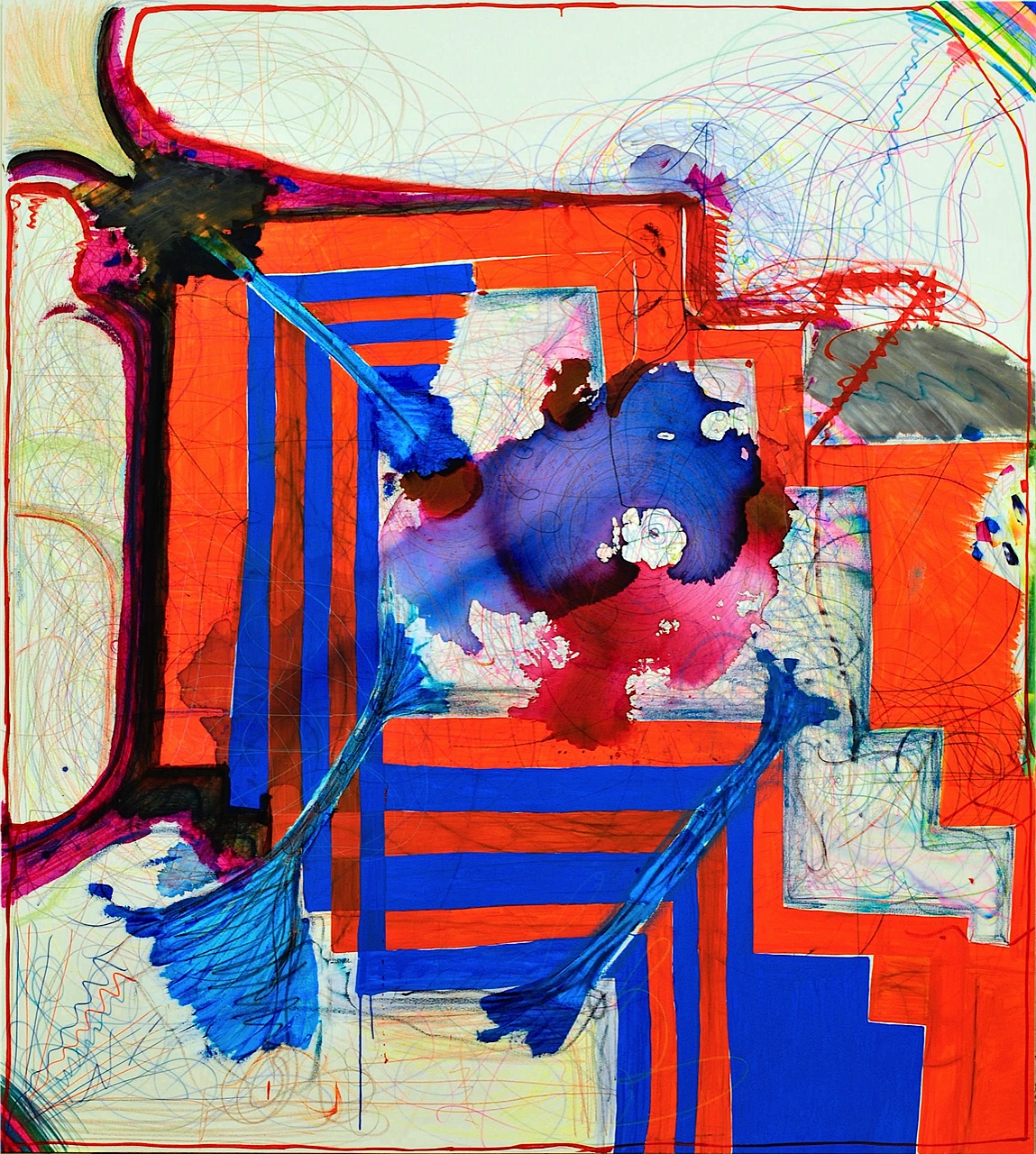

In every one of these paintings I start by filling up the surface with marks and then I look at it and find some shapes, and then it just starts taking off and becoming it’s own life force. In this one (Moma…Please), the marks on the whole right side then became part of the finished painting. In some of them it’s completely hidden, you don’t see those original marks anymore. And in that one, there’s still some. So that’s the beginning point, and that’s why I think every one is so different, because the marks are different and then I interpret them differently in each painting.

In this painting (Stone Memories) there is the original gesture, and I put some washes over it and then it looked like a figure which seemed important. And then when the other shapes emerged, I knew it was a mother and child at that point. And that’s how it got the title “Stone Memories.” In a lot of my work I have an observer that’s watching and there’s a balancing act that’s going on–

And a pulling or resistance…

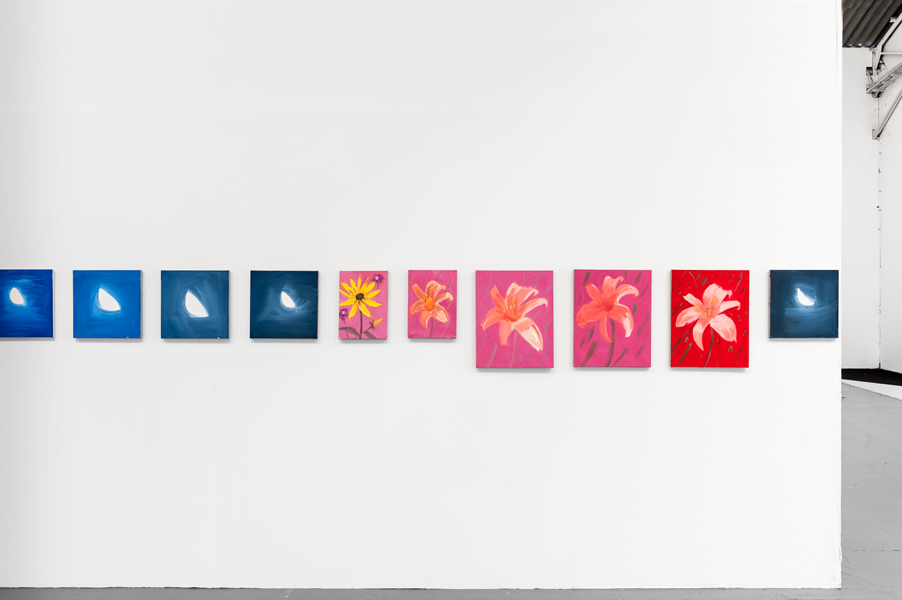

Yes, I like those dualities. In my last show I did a couple of small ones with the grid, and then I moved into these new paintings.

I thought Almost A Bride was finished in an earlier stage. It was more of a cross form, it had a figure, but a few people saw it and I got a ho-hum reaction. I usually pay attention to people’s reactions, if one person doesn’t like it and five people do, I’ll listen to it but I’ll go with what I feel. But for this one there were a few people who just didn’t respond well to it and then I looked at it and it I knew I hadn’t developed it enough. It was a cross but I knew it didn’t have the complexity I wanted. I felt like I could do more to it. So I went into Photoshop and I started experimenting with how to change it, Photoshop is very helpful to work out some ideas. And I decided to rework it. So I got rid of the arms of the cross…It got me mad that I didn’t see it myself! Because most of the time I see these things myself. But I changed it and I worked on it, and look what I got!

As far as the screen form goes–I wanted to emphasize it more, I wanted that form to be more dominant. And then all those formal decisions – my work is as much about emotion as it is about formal issues. (I have a very traditional background, my painting teacher wouldn’t let us use paint for the first six months, we had to use thumbnail sketches and then we had to use earth colors and then eventually we were allowed to use color.) I learned the fundamentals of painting inside and out and I still believe in them. And I always use deKooning as an example. You can be as free and emotional as you want but then you have to go in and light up your cigarette and make some formal decisions! Those clean, sharp lines, like in the women series, those were there to clarify the chaos around it, they were very intellectual, formal decisions.

Those paintings had both the emotional and the formal held really intensely together, you could feel the painting-mind at work and the thinking through but that didn’t cloud or distance that feeling of fear of women, the mother issues, those were all right at the surface.

That was the initial impulse, but then he sat back and said okay, there’s areas here where I have to make this a better painting, it can’t just be about this – although he would probably deny all those things you said–

It’s all over that work!

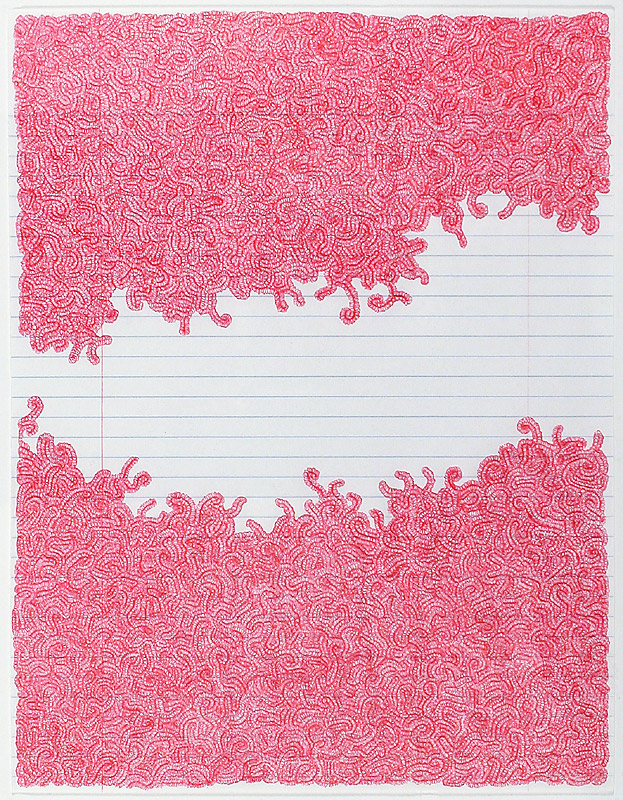

Yes, those are important things! And I think you see so much work now that lack depth and rigor. There’s not a lot revealed. No risk, no presence, just tossing one out after another, posting eight of them a day to social media, and getting the wows and going onto the next, and I hate that. It has to be more than that.

My life has been full of people who feel they receive something from my work. I did a series of empty room paintings in the ’80’s and they always had a little chair in it or a little something to say this is the story, and then there was one where it was completely empty with only a small shape and there was an opening and light coming in and onto the floor, it was very simple. And a friend of mine, who was dying of bone cancer bought that painting, she said that it gave her a place where she felt peaceful.

And I thought at that point that I could throw my brushes away! I’ve arrived at something important. And I guess I just feel that there’s so much work that’s just empty. There’s nothing there and there’s no risk, just ‘nice.’ And I think how long it took me in years to let go of a precious shape in a painting–you’ll relate to this, every artist will relate to this–you work around it and you work around it and you change this and you say to yourself – that area, I can’t let go of that area, it’s just so wonderful, everyone is going to love it, and I love it! And you go nowhere with this painting until you’re ready, and then you eventually have to give up that shape, and as soon as you give up that shape, guess what–

Haha, the painting gets a lot better!

The painting finishes itself in 10 minutes—and you feel like “oh, how did that happen? What’s all this called?” It’s called trust and surrender. And so, in the old days when I would have one of those areas it would sometimes take a week or a month to give it up because there’s so much will involved.

It takes a lot of artists even longer than that!

Yes, and then once you give up that area and it all falls in place, then you say: “oh, I wonder if I’ll do that again!” And it happens again and it stills takes a long time to give it up, and you’ll say to yourself, “it happened again!” And so fifty years later, when that happens to me, I know in a matter of minutes, maybe an hour, and then I know what I have to do. I think one of the most important processes of being an artist is how long it takes you to let go of your ego and surrender to the piece and trust that it’s going to be a better painting, and that’s huge. How long does it take you?

It depends on the painting.

How old are you?

I’m 30, about to be 31.

I’m 41 years older than you. So how long does it take you?

It depends on each one.

Well, approximately.

Each one is pretty different, but I’d say a week, two weeks, a month or so – it’s a whole range.

But you know the feeling.

Oh yeah, of course! It’s obnoxious. But it’s really interesting too because it also feels like the key to the painting. And so much of it is like, as you’re saying, dancing around resistance, but in paying attention to that you may end up with some other interesting things. It’s always in the back of the mind, knowing that you’ll have to go there eventually, but I’m not quite ready or I don’t feel like it, or I know it’s going to be a battle–

You can talk yourself out of it, it’s easy to do.

There was one painting that I did in ’85 that was in a show at Ed Thorp’s, and the whole painting was almost done, it was just one area that was not working and I was afraid to do anything to it, and yet I didn’t like it. I felt like I was in the darkest hell that one could possibly be in–the abyss was so dark and so deep and I didn’t think there would be light at the other end of it, although there always is, I didn’t think there would be light, and once I let it go it fell into place and that’s painting is called the Breakthrough–

It’s so educational, having those experiences, and they’re not all like that.

Of course not. That painting sort of painted itself. Some of these paintings don’t paint themselves.

Do you work with palette knives in addition to brushes? The textures of these paintings are so varied.

When I was a student I wanted to experiment with different textures and materials right from the beginning. And I would take all these notes on all these materials that I used to mix in the paint and through the years it’s just sort of become my specialty. I wanted to experiment with as many different tools and stuff to do my paintings because I feel that the more ways you can handle the paint with as many tools as possible you have more ways to communicate your feelings. I also want people to think they’re as wonderful close up as they are far away. Sometimes if you only know how to use wash brushes and make pretty skies and you want to make a dark intense something-or-other, how are you going to do it? You have to stop your practice and go learn a new technique, which might take a day or it might take two years. I don’t want to do that, so I learn all these things as I go along.

There was a series of big triptychs I did in 2002 that have a lot of washes—I was watching television and happened to see a program about home and gardening, there was a woman on a ladder with one of those foam rollers and she was painting bamboo leaves. So the next time I went to the hardware store, I got a couple of those. And all of a sudden all this new stuff started to happen in the work, like I was able to put a warm and a cool wash wet in wet in a whole different way. So over the years I’ve built up techniques and tools, for those thick marks I have cake decorators with different tips and I have squeegies and I have foam brushes and I have foam rollers and I have Q-tips and I have palette knives—I just use whatever I feel I need to use. Also I mix pumice and ashes from our wood stove into some of the surfaces. I use whatever I think is going to work emotionally—like for these grid forms/screens, I squeezed the black out of a small plastic bottle.

I can really tell!

But I knew it was going to create a certain feeling, so I had to do it. And contrast is extremely important to me too. Busy, active, surface variation–all those formal things, thin, and thick. When I was a student I would paint one side of a wall with sand and the other I would glaze, and yet visually it held together, and that was a real challenge. And I still think about things like that—how many different things can I do and still make it visually work and create the feeling that I want? So materials and tools have always been a really important part of my process, I spend a lot of time preparing my studio setup. I have really thin white oil paint, I have thicker white paint, so it’s all ready to use as I need for a particular painting.

Is there a risk of taking the emotional/feeling part of making these painting too far and into a kind of therapy? Is it about changing how you feel or is it about working through or resolving it or is it something else?

Good question. No one’s ever accused me of using my work as therapy.

It came up in one of your other interviews from 2010, the one with David Brody for Artcritical. You were talking about this painting (Self Portrait 16, 2005), and he said: “It’s refreshing to hear an artist so committed to the painting process and the materials of painting talk about a therapeutic value to art…” So I was wondering about that, do you feel like when you’ve worked on something that it’s solved therapeutically for you?

It’s happened a couple of times. Sometimes early on some people said I was using art as a cathartic thing, because it was right on the edge. There’s only been two times when my painting changed something in me. I wish it was more often but I guess that’s not bad in terms of one’s work.

One was when my mother died on my birthday when I was 29 and she was 52. When I turned 52 I got really angry at her because I was afraid I was going to get everything she had, because those are what genes do. I started to do a series of paintings that I thought were going to be very angry and ugly, and all of a sudden I was using all these bright colors and I had no idea where all of that was coming from! And my mother loved color and I didn’t. I was using a lot of praying figures at the time and I was also anchoring in a combination of the abstract and the figurative. So I started using all these colors and I thought, “this isn’t right, these are supposed to be dark and ugly!” And then I realized that when I was doing them that the color was for my mother. Something released in me, and the series became “Songs for My Mother” instead of “You Bitch,” or whatever else. I never felt that particular anger or resentment or fear of her illnesses again. It released me of feeling all of that.

And then the second time was that painting, Self Portrait 16—she was not a warm, affectionate mother. Her own mother died when she was five years old, she was raised by her sisters, I never touched anyone or hugged anyone either, and I was just like her. She got lung cancer and when she was dying in bed in the hospital, I didn’t even know to be able to sit down next to her and hold her hand. So that little character at the end of the bed, that yellow one, was me watching her. She had an oxygen thing over her and she died. And it was in this series in 2005 where I finally dealt with that, I wanted to paint that. And recreate it and see if I could heal it. So I painted that painting and put myself next to her bed and held her hand. With the other character still there just watching, but it healed something in me. I couldn’t do it while she was alive.